| Back |

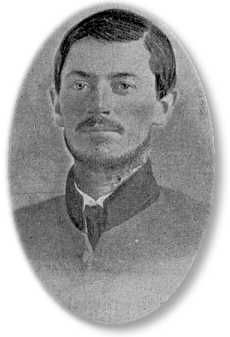

DeWitt (Dee) Smith Jobe

"A Martyr of War"

Pvt. Dee Jobe, who had just turned 24 in June, was near Nashville, probing for information, speeding it southward. With him had come Tom Joplin and other Coleman Scouts. They were operating around College Grove, Triune and Nolensville. Danger didn't matter. They knew what had happened to their fellow scout, Sam Davis.

And say, on nights when the dark clouds toss, Can you hear the clatter of a runnin' hoss? Oh, Lawdy! What's the matter? But nobody talks. The clatter stops and the ghost hoss walks. It's the Yankees teachin' Dee Jobe who's boss. ... At the point of 15 guns. Days hence, the news would reach DeWitt Smith, Jobe's cousin and friend, of the 45th Tennessee Regiment. They had been close companions and may have been namesakes. Smith's mind would become "unhinged' when he heard it. He would break away from Hood's army and "run up the black flag." That is, he would vow to take no prisoners; to kill every Yankee he met. Smith would come riding back into Middle Tennessee as the avenger. Many a Yankee, as many as 50 of them some said, would die in the night, his throat quietly slit with a butcher knife. The August sun is sinking. A spring wagon is creaking through the shadows. Old Frank, the Negro slave who had tended Jobe as a child, is driving. His cheeks are wet as he lifts his young master's body, places it in the wagon, and heads back to the big log house where Jobe was born, June 4, 1840. Today a roadside marker speaks of Jobe, on U. S. Highway 31A in Williamson County between Triune and Nolensville: "DeWitt Smith Jobe, a member of Coleman's Scouts, CSA, was captured in a cornfield about 1 1/2 miles west, Aug. 29, 1864, by a patrol from the 115th Ohio Cavalry. Swallowing his dispatches, he was mutilated and tortured to make him reveal the contents. Refusing, he was dragged to death behind a galloping horse. He is buried in the family cemetery six miles northeast." No granite shaft stands tall today to mark the spot of the Middle Tennessean who wouldn't be brain-washed. On a lonely little knoll he sleeps, where visitors seldom go, near the site where he was born. There is no inscription on the stone. The night of oblivion has almost closed in. Ask anyone, who was Dee Jobe? And the answer may be, "I don't know what you're talking about." The preceding narrative was adapted from "The Civil War in Middle Tennessee" by Ed Huddleston. Originally published as a series of supplements to the "Nashville Banner" in 1965, the series was later assembled and published in book form. In the years that have passed since this was written, the resting place of Dee Jobe has come under the care of the William B. Bate Chapter of the MOS & B, and now receives perpetual care. The grave is located on private property - a farm a few miles off the Smyrna / Almaville Road exit of I-24, about 20 miles southeast of downtown Nashville. Some years ago, a Sam Davis Camp member and Real Son, Robert Herbert, whose father also rode with Coleman's Scouts, installed an appropriate marker at the grave. |

HOME

About SCV -

Join SCV -

Legionary -

Co. News -

Education -

Ancestors

Memorials -

Links -

Guest Book