|

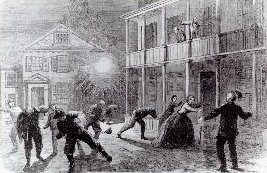

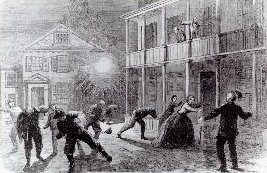

During the Summer of 1864 both Federal and Confederate heavy artillery mortar shells flew back and forth over Charleston Harbor enroute to their intended targets. Even the city, populated by civilians, fell victim to this death from the sky.

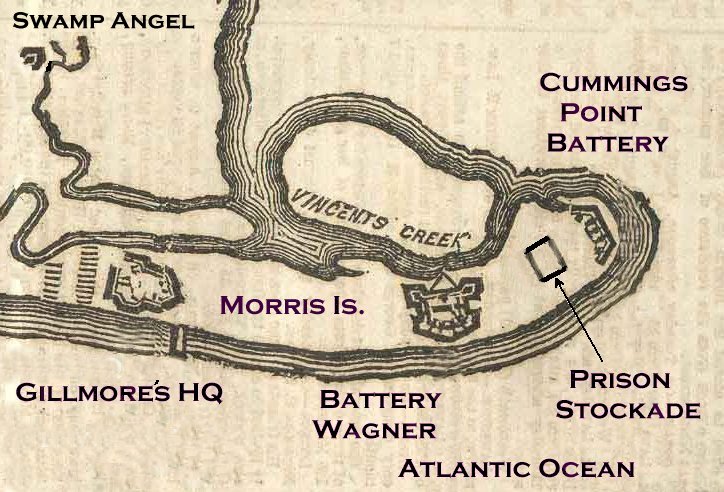

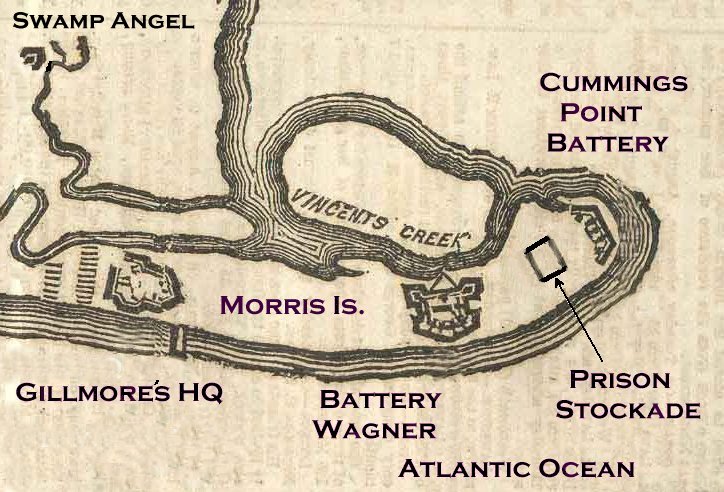

In the midst of this tumult an unfortunate group of Confederate prisoners were living in a stockade built in the path of those bombs, their Morris Island prison pen had been deliberately placed in harm's way. In essence, these beleaguered confederate prisoners, baking in the sun, were being used as human shields. It was a sad commentary on how nasty the Civil War had become.

Knowingly exposing helpless prisoners to artillery fire seems unconscionable.

War, however, has a way of fostering inhumane behavior.

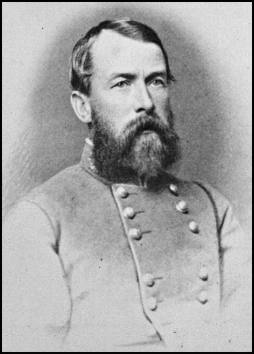

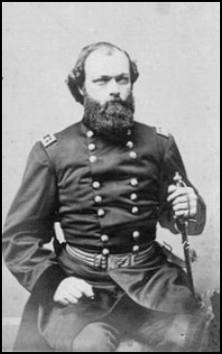

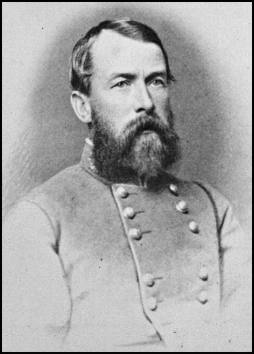

Gen. Q. A. Gillmore |

|

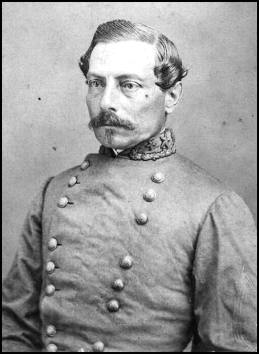

This inhuman situation had its start the previous summer. On August 21, 1863, Maj. Gen. Quincy A. Gillmore, the Federal commander in the Charleston area at the time, had sent a message to General P.G.T. Beauregard, informing him of the Union army's intention to fire into Charleston because he considered it a military target. He informed the General Beauregard that the shelling would start sometime after midnight, August 22.

Beauregard protested, stating that he did not have adequate time to evacuate the city of its noncombatants. Nevertheless, the next morning, Federal mortars sent their deadly projectiles into both the residential and business areas of downtown Charleston.

|

|

Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard |

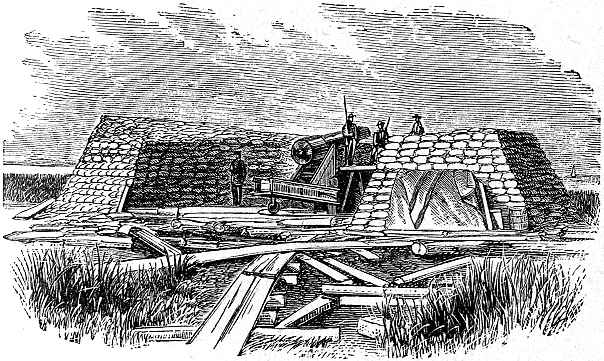

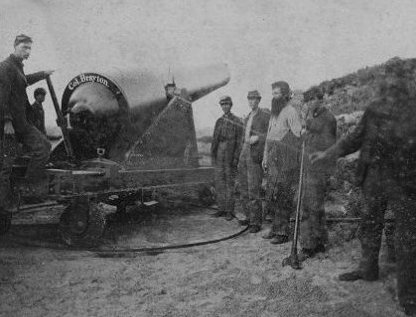

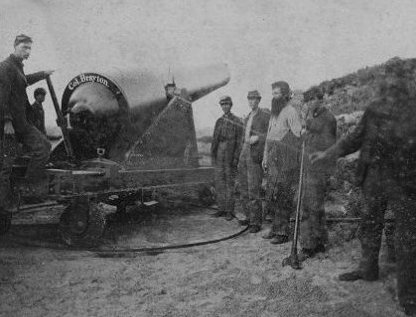

Gillmore placed an 8-inch Parrott rifle in the marsh between Morris Island and James Island four miles from the city. The cannon, nicknamed the "Swamp Angel," fired 16 shells into Charleston before dawn, starting a bombardment that would last 567 days. In the month of January 1864 alone, 1,500 mortar shells were fired into the city.

Federal 8-inch Parrott Rifle Battery "Swamp Angel" |

|

Bombardment of Innocent Civilians |

On April 20, 1864, Maj. Gen. Samuel Jones arrived in Charleston to take command of the Department of South Carolina, Georgia and Florida from Beauregard, who had been reassigned to North Carolina.

| |

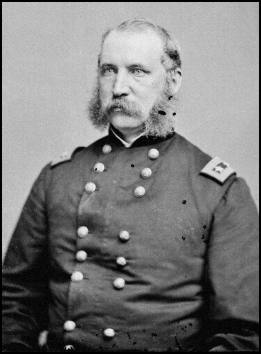

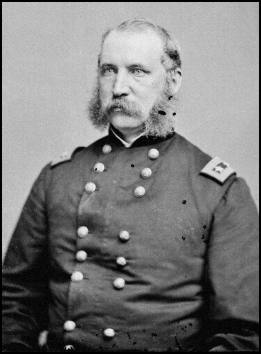

Maj. Gen. Samuel Jones |

|

At the time of Jones arrival, the battered city had already endured eight months of bombardment. The Federal artillery had caused irreparable destruction throughout the city and the streets were pockmarked with craters and littered with the bodies of unburied animals.

Shortly after the Southern change of command, the Union also assigned a new man to Charleston. On May 26, 1864, Maj. Gen. John Gray Foster replaced Gillmore as the head of the Department of the South. Foster realized that he lacked the means to successfully assault or outflank the massive defenses of the harbor town, and settled into continuing the siege by bombardment.

|

|

Maj. Gen. John G. Foster |

|

Lacking the manpower and resources to drive Foster's Yankees away, General Jones looked for immediate ways to alleviate the bombardment. He turned to drastic measures to do so. On June 1, 1864, he requested from Jefferson Davis, that 50 Federal prisoners be sent to him to be "confined in parts of the city still occupied by civilians, but under the enemy's fire." Davis approved his request, and on Sunday, June 12 the unfortunate prisoners arrived by trains from Camp Oglethorpe in Macon, Ga.

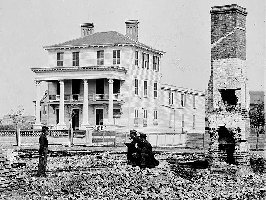

The fifty (50) unlucky Yankees, all officers, five of them brigadier generals, were placed in a home converted into a prison in the south end of Charleston.

Jones sent a note to Foster to tell of the captives' arrival and that they had been placed in "commodious quarters in a part of the city occupied by non-combatants....I should inform you that it is a part of the city…for many months exposed to the fire of your guns." This action set in motion a chain of events that would endanger the lives of helpless prisoners of war and outrage the highest officials of both governments.

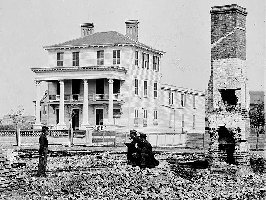

| |

The Federal Officer Prisoners were housed in the O'Conner House in the city

~ Click for a larger image ~ | | |

|

Foster immediately requested that 50 Confederate officer prisoners be sent from the prison at Fort Delaware and placed in front of the Union forts on Morris Island in retaliation. He sent a letter to Jones in which he argued that Charleston had munitions factories and wharves for receiving goods run past the blockade. He stated that to "destroy these means of continuing the war is therefore our object and duty. You seek to defeat this effort, not by honorable means, but by placing unarmed and helpless prisoners under our fire."

Jones was insenced and fired back a letter chastising Foster and the Federal armies for their conduct throughout the war. He closed his dispatch with these words:"Under the foregoing statement of facts, I cannot but regard the desultory firing on this city which you dignify by the name bombardment, from its commencement to this hour, as antichristian, inhuman, and utterly indefensible by any law, human or divine." Jones was in no mood to be chastised by his opponent.

In late June, the war of words began to match the war of guns, but the stalemate dragged on and the prisoners stayed put.

Five Federal generals wrote to Foster requesting an exchange and asking that the Union provide the Confederate prisoners with "kindness and courtesy."

Jones reminded them that as of April 1863 the Federal government had ended the practice of exchanging prisoners. The new hard-line policy was designed to prevent soldiers from returning to the ranks of the Southern armies. It also, however, caused a rapid swelling of the numbers of men in Northern and Southern prisons.

President Abraham Lincoln became aware of the situation in Charleston and gave permission to Foster to make an exception to War Department policy and begin making arrangements for an exchange. Thus, on August 3, an agreement was worked out for the exchange of 100 officers.

Just when it seemed that the prisoner dispute had been resolved, things took a turn that would place even more captives in harm's way. Sherman's campaign in Georgia was getting too close to the overcrowded prison camp at Andersonville, So these prisoners were sent to Charleston. Jones objected, arguing that it was "inconvenient and unsafe."

Foster was furious when he heard of the new prisoner shipments, thinking that they had also been sent to the city to serve as human shields. He wrote Jones that he would place Confederate officers "under your fire" to retaliate. Construction began on a Union stockade in front of Battery Wagner on Morris Island and directly in the path of Southern artillery, and Foster ordered 600 Confederate officers removed from Fort Delaware.

Fort Delaware Sally Port | |

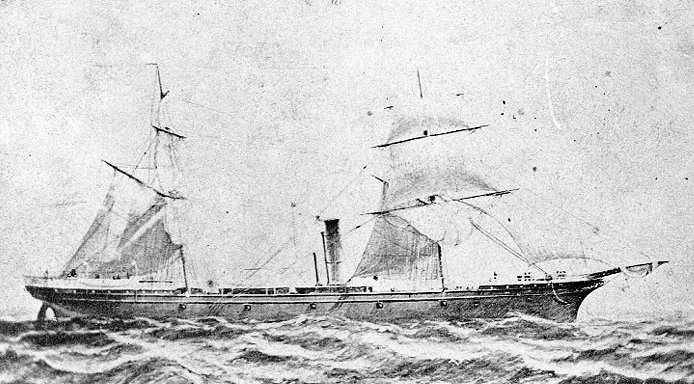

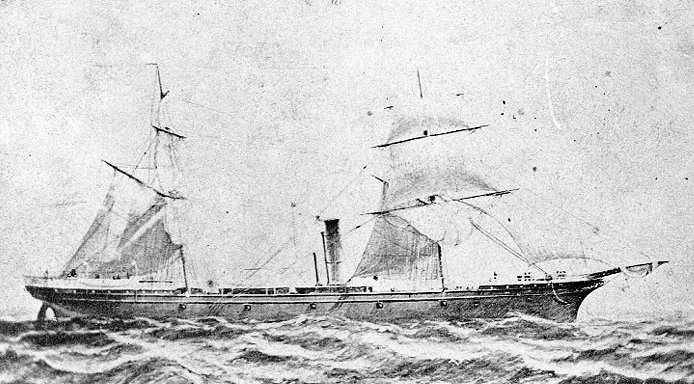

USS Crescent City |

On August 20, the Federal steamer Crescent City left Fort Delaware with its cargo of 600 Confederate officers packed into the fetid hold and shipped south in the blistering summer sun. Lieutenant George Finley of the 56th Virginia Infantry remembered sitting in "total darkness, without any clothing and drenched with perspiration."

He ate but a "few crackers with a bit of salt beef or bacon"

during the journey. The prisoners remained on Crescent City near Hilton Head while the stockade on Morris Island was completed.

The Confederate War Department, meanwhile, kept sending prisoners to the Charleston area. Jones was now anxious to make exchanges, and news of a pending deal reached the headquarters of Gen. Grant, the overall Federal commander. Gen. Grant had long been among the leading advocates of ending exchanges and his opinion prevailed in Washington. The situation in Charleston intensified when General Sherman's forces captured Atlanta and threatened Andersonville so captured Yankees continued to pour into the Charleston area.

. |

|

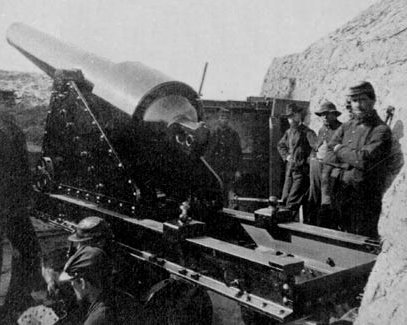

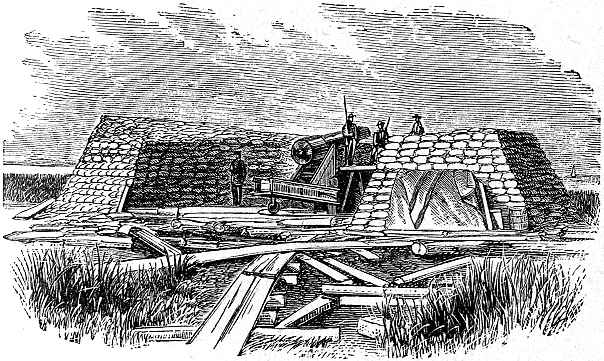

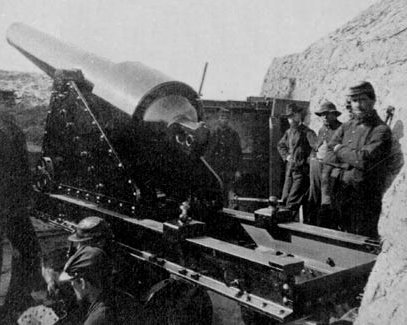

Federal Batteries on Morris Island |

|

. |

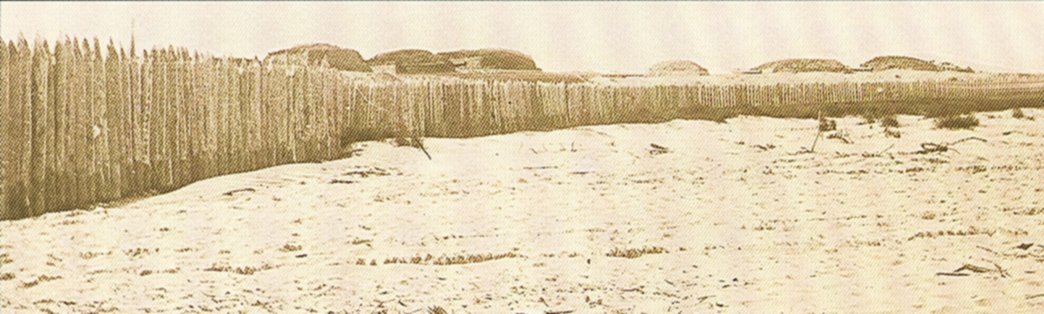

On September 7, the Federal stockade on Morris Island opened and was quickly filled with the Confederate prisoners, numbering a little less than 600 due to deaths from disease. At night they were subjected to clouds of sand fleas and mosquitoes and drenching thunderstorms, The Federals did not issue blankets, and the men were forced to sleep in the sand. All the while, they were exposed to cannon shells and the scorching summer sun. The big Federal guns in Battery Wagner would blast shells over their heads, and occasionally one of the rounds would prematurely burst, scattering the camp with fragments.

It was even more terrifying when the Southern gunners replied to the Union salvos and sent inbound projectiles directly over the prisoners' camp.

Stockade for Confederate Prisoners on Morris Island. |

~ Click for a larger image ~

As reports of the arrival of the Confederate officers in the stockade on Morris Island reached Confederate headquarters, Jones suggested on September 7 that "If the department thinks it proper to retaliate by placing Yankee officers in Sumter or other batteries, let the order be given, prompt action should be taken. Please instruct me what if any authority I have over prisoners."

|

Throughout the month of September, the shelling continued, and the Confederate captives remained in their prison pen. Several Union guards were struck by shrapnel, but, almost unbelievably, the prisoners remained unharmed, even though approximately 18 rounds, all duds, actually landed in the stockade. The prisoners' rations usually consisted of only two pieces of hardtack a day. On a good day, a prisoner might receive some

"worm eaten hard tack, a little chunk of bacon one half inch square"

and a bowl of bean soup made, it was rumored, on a formula of

"three beans to a half quart of water,"

remembered Thomas Pinckney, a captain in the 4th South Carolina Cavalry.

| |

|

|

General Jones' threats to put Union prisoners on the ramparts of Fort Sumter never materialized, and on October 8 the Union captives in Charleston were removed to cities farther inland.

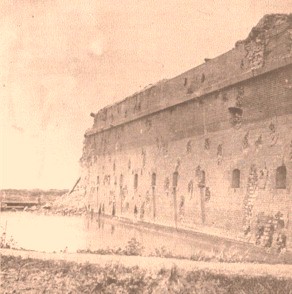

The Southern captives' ordeal continued, however, until October 21, when, after 45 days of exposure to shellfire, they were finally taken out of their miserable pen and transferred to Fort Pulaski at Savannah, Ga.

Fort Pulaski after surrender | |

Prison Cells | |

Prisoner Burial |

The men spent a miserable cold, dreary winter there, 13 dying of disease. In March, the survivors were shipped back to Fort Delaware, where 25 more succumbed to illness. There they remained until after the war ended. The last man of the group was not released until July 1865.

The harsh and unusual conditions of their imprisonment inspired one of the captives, John O. Murray, to record his experiences in the 1905 book The Immortal Six-Hundred. The name he gave the group stuck, and today they are still referred to as the "Immortal 600."

Samuel Jones was transferred to Florida after Charleston finally fell in February 1865. He died in 1887. Foster remained in Charleston until the city surrendered. He died in New Hampshire in 1874 and received a hero's funeral from the people of the Granite State.

Both generals had felt compelled to resort to tactics they knew were against the code of honor they had learned at West Point, yet both felt that under the circumstances they had little choice. Behind their decisions were the emotions of hatred for an enemy they had come to loathe, and the callousness that comes when the sight of destruction and death becomes commonplace.

It is difficult to say who was at fault for the fiasco. Jones was the first to place prisoners under fire. On the other hand, the Federal Army was firing into a city where they were well aware civilians still resided. Grant must also shoulder some blame, for his orders ceased the prisoner exchanges.

No matter who should bear the burden of responsibility, the treatment of the prisoners in Charleston Harbor, particularly that endured by the Immortal 600, remains one of the most controversial incidents of the Civil War. Certainly, the prisoners-as-shields practice constitutes a dark chapter in the greatest of American tragedies.

|